Originally written: 11 July 2020

Last updated: 29 October 2021

Last updated: 29 October 2021

We often receive requests from English-speakers for more information about Ryukyu. Unfortunately reliable resources about Ryukyu are hard to come by, particularly in the English language. American and Japanese scholars, mass media, as well as the general public, often perpetuate false or misleading information about Ryukyu. Some Japanese supremacists (ネット右翼) pretend to be Okinawans online, and purposely spread false information about Okinawa.

With that being said, The Peace For Okinawa Coalition and other Ryukyuans are trying to produce more information about Ryukyu written by Ryukyuans, including videos, books, articles, film, etc.

For now though, this webpage is intended to provide an introduction to Ryukyu written by Ryukyuan scholars in the English language. This page will continued to be revised and updated.

With that being said, The Peace For Okinawa Coalition and other Ryukyuans are trying to produce more information about Ryukyu written by Ryukyuans, including videos, books, articles, film, etc.

For now though, this webpage is intended to provide an introduction to Ryukyu written by Ryukyuan scholars in the English language. This page will continued to be revised and updated.

Contents

- Basic Facts

- Names

- Languages

- Prehistoric and Ancient History

- The Gushiku (Gusuku) Period

- The Three Kingdoms Period

- The First Ryukyu Golden Age

- The Satsuma Invasion of 1609

- The Second Ryukyu Golden Age

- The Annexation by Japan

- The Battle of Okinawa

- Modern Ryukyu

- Recommended Further Reading

Basic Facts

Ryukyu consists of roughly 160 islands, 60 of which are inhabited at any given time.

琉球

|

English name: Ryukyu

National Anthem: 石投子之歌 (Ishinagu Nu Uta) Capital: Shuri Largest City: Naha Languages: Ryukyuan, Chinese Ethnic groups: Ryukyuan Land area: 2,271 square kilometers (877 square miles) Population: 2.1 million Ryukyuans worldwide 1.4 million Ryukyuans in Ryukyu 700,000 Ryukyuans overseas |

Names

Since time immemorial, Okinawa was an independent country known as 琉球,Luuchuu or Ryukyu. The use of the roman alphabet is relatively new for Ryukyuans, so there is no one single universally-accepted "correct" way of spelling Ryukyu.

After Japan invaded and illegally annexed Ryukyu in 1879, it changed Ryukyu's name to "Okinawa" in an attempt to erase Ryukyu's history as an independent country. Japan did similarly to most of the other countries it invaded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

After Japan invaded and illegally annexed Ryukyu in 1879, it changed Ryukyu's name to "Okinawa" in an attempt to erase Ryukyu's history as an independent country. Japan did similarly to most of the other countries it invaded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

|

琉球 = Traditional Chinese characters

Liuqiu = Chinese romanization Lequeos = Portuguese spelling Lequios = Spanish spelling Lekeyo = French spelling Loo Choo = British spelling Lew Chew = American spelling Ryukyu = Japanese & modern American spelling Luuchuu = Modern Uchinaaguchi spelling Duuchuu = Alternate Uchinaaguchi spelling All of these spellings are considered correct and are often used interchangeably. Today "Okinawa" is the more commonly known name in Western countries, thanks to Japanese propaganda, though 琉球 (Ryukyu) is still more commonly known among non-Western countries, particularly among most Asian countries. |

|

Languages

The Ryukyuan languages are the Indigenous languages of Ryukyu as recognized by UNESCO, scholars, and most countries around the world. The Japan government refuses to recognize the Ryukyuan languages, instead referring to them as "dialects of Japanese," similar to what they did to the Korean language during Japan's occupation of Korea. The Ryukyuan languages are unintelligible with Japanese.

|

|

|

According to modern linguists, there are ten different Ryukyuan languages, all of which are mutually unintelligible from each other:

There are also hundreds of different dialects of these languages that vary by village and/or island.

- Kikai

- Amami

- Tokunoshima

- Okinoerabu

- Yoron

- Kunigami

- Okinawa

- Miyako

- Yaeyama

- Yonaguni

There are also hundreds of different dialects of these languages that vary by village and/or island.

|

An Indigenous form of writing was in use in the Yaeyama Islands, though it never became in widespread use throughout Ryukyu. It was used mainly by merchants for record keeping. Suzhou numerals were also used.

This writing system is now called the Kaida Glyphs, and can be seen on t-shirts and other merchandise. |

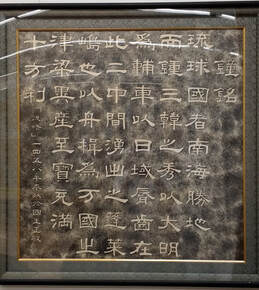

Inscription from the Bridge of Nations Bell, written in Classical Chinese.

Inscription from the Bridge of Nations Bell, written in Classical Chinese.

Instead Ryukyuans adopted Chinese as their preferred writing system by at least the 13th century. Most historical Ryukyuan documents prior to 1879 were written in Classical Chinese. Many or most Ryukyuan scholars, government officials, and traders adopted Chinese as a second language, and used it as a lingua franca throughout East and Southeast Asia. To this day, some Ryukyuan ceremonies are still done in Chinese.

|

|

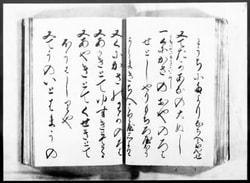

Umuru Sooshi (Omoro Sooshi)

Umuru Sooshi (Omoro Sooshi)

Kana was also imported, from Japan, and sometimes used, primarily for poetry or annotations. Most famously, hiragana was used to write in Uchinaaguchi (the Okinawan language) the Umuru Sooshi (Omoro Sooshi) - a collection of 1,553 poems that had been passed down orally since ancient times. It was compiled in writing in 1531.

Japanese was rarely used, and usually only when communicating with Japan.

After Japan invaded and illegally annexed Ryukyu in 1879, it began the forced teaching of the Japanese language in Ryukyu's schools. However, Japanese did not become spoken outside of the classroom until many decades later, despite Japan's harsh attempts to stop the speaking of the Ryukyuan languages. The Ryukyuan languages continued to be used throughout Ryukyu until the 1970s. In 1972 the United States "gave" Ryukyu to Japan, and since then Japan has instituted harsh policies in an attempt to eradicate the Ryukyuan languages, all of which are endangered. It is estimated that around 25% of the population still speaks a Ryukyuan language.

Today most Ryukyuans are able to speak Okinawan Japanese, which is an Okinawan-style dialect of the Japanese language. It is similar to how locals in Hawaii speak Hawaiian Pidgin English. Okinawan Japanese is generally intelligible with standard, Tokyo Japanese, though contains notable differences, along with many Ryukyuan loan words. It can be difficult for Japanese people and Ryukyuans to understand each other. In fact, many young Ryukyuans today are unaware that a lot of the words they use in their everyday vocabulary are actually Uchinaaguchi (Okinawan) or Ryukyuan. Thus while many young Ryukyuans might not be aware that they are speaking Uchinaaguchi (or one of the other Ryukyuan languages), they know more than they think they do. Unfortunately, even Okinawan Japanese is stigmatized by many Japanese people, who look down upon and make fun of Okinawans who speak this.

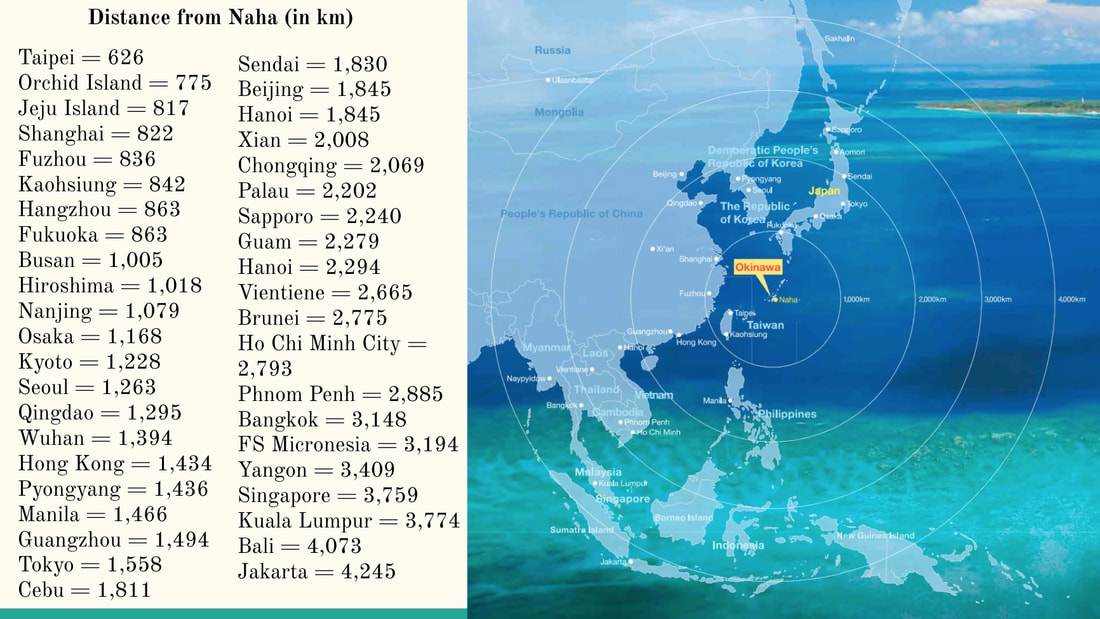

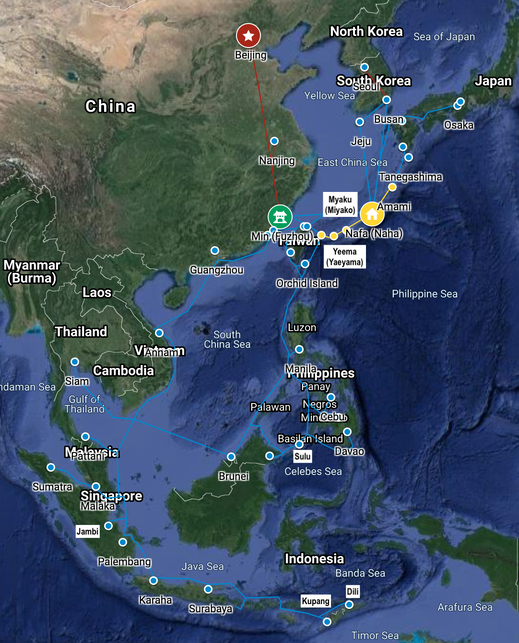

Many people have a mistaken belief that Ryukyu is geographically close to Japan, when in actuality, Ryukyu is much closer to China. Ryukyu is actually much closer to the capitols of South Korea, North Korea, and the Philippines, as well as to many major Chinese cities, than it is to Tokyo.

Prehistoric and Ancient History

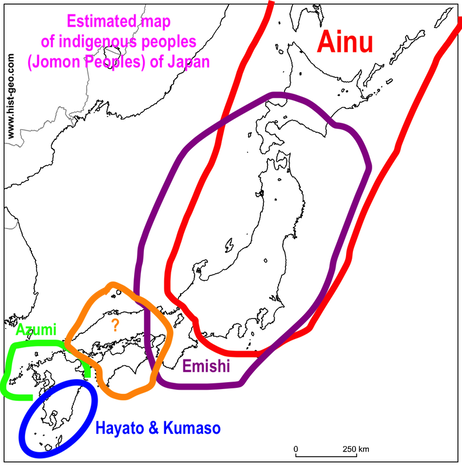

Ryukyuans are the Indigenous peoples of Ryukyu. According to archeologists, Ryukyuans have lived in Ryukyu for at least 32,000 years. Ryukyuans are genetically and culturally close to the Jomon Peoples (the Indigenous peoples of Japan), such as the Ainu.

Map of the estimated locations of the Indigenous (Jomon) peoples of Japan, prior to colonization by the Yayoi (Modern Japanese) starting around 2,000 years ago. Today many of Japan's Indigenous peoples have been killed off, and the northern island of Hokkaido remain the last major population center of the Ainu.

Courtesy of Robert Kajiwara.

Scholars have also identified strong links between Ryukyuans and other Austronesian peoples, such as the Yami of Tao (Orchid Island), and the Indigenous peoples of Mindanao (Philippines).

Below: Four styles of traditional Ryukyuan thatched buildings.

According to Ryukyu history, the first Ryukyuan was Amaminchu, who was ordered by Heaven to populate the Ryukyu Islands. Amaminchu is said to have been placed by Heaven on the island of Kudaka along with her husband, Shinirinchu. They are the ancestors of all modern Ryukyuans. To this day Kudaka is the most sacred island in Ryukyu, and is the destination of many pilgrimages.

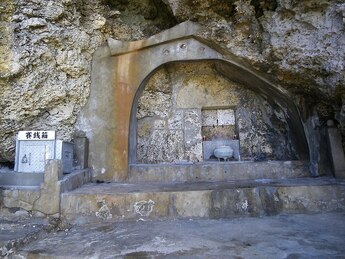

Amaminchu and Shinirinchu eventually moved to Uchinaa Island (Okinawa Island), arriving at Sefa Utaki, a natural rock formation with a 90 degree angle. Sefa Utaki is considered the most sacred grove on Okinawa Island. They had children and grandchildren, who eventually spread out over the Ryukyu Islands.

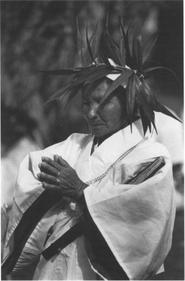

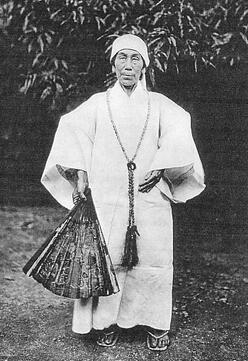

Tenson, one of Amaminchu's descendants, become the first king or chief of Ryukyu, founding the Tenson Dynasty, which is said to have lasted for 25 generations. Although the position of king or chief was held nominally by men, much of the actual power was held by women who served as priestesses called Nuru (commonly called Noro in English and Japanese today). Early Chinese and Japanese accounts marveled at what they referred to as "Island countries ruled by Queens."

In one famous instance, the head priestess of the Ryukyu Kingdom "recommended" the king step down in favor of his younger nephew. The king obliged without conflict, and the new king took the throne, and ended up being one of the most successful kings in Ryukyu history.

The tradition lasts to this day, with men seen as the "secular" leaders and women seen as the "spiritual" leaders. Due to the strong nature of females in Ryukyu society, Ryukyu is sometimes referred to as a matriarchy or semi-matriarchy.

In one famous instance, the head priestess of the Ryukyu Kingdom "recommended" the king step down in favor of his younger nephew. The king obliged without conflict, and the new king took the throne, and ended up being one of the most successful kings in Ryukyu history.

The tradition lasts to this day, with men seen as the "secular" leaders and women seen as the "spiritual" leaders. Due to the strong nature of females in Ryukyu society, Ryukyu is sometimes referred to as a matriarchy or semi-matriarchy.

The southwestern most Ryukyu Island of Dunan (Yonaguni) may have had an advanced society during ancient times (before 1000 B.C.E.) that later become submerged due to earthquakes. This is referred to as the Yonaguni Monument. Some have likened this as inspiration for the "Lost City of Atlantis" or "The Lost Continent of Mu." More research needs to be done and it is unclear whether or not the Monument is natural or manmade.

|

Archeological evidence indicates that early Ryukyuans had trade relations with China, the Philippines, and the Jomon people of Japan. Ryukyuans often traded shells in exchange for pottery or other items. Shells at the time were widely used in Asia and the Pacific as a form of currency.

This is sometimes referred to as Ryukyu's midden or shell period. Even in these early times, Ryukyuans thrived with easy access to a plentiful amount of ocean foods, such as fish, shellfish, seaweed, and others. |

According to archeological evidence, Ryukyuans likely had trade relations with China by at least the Zhou Dynasty. Coins believed to be from the Kingdom of Yan (燕 - northern Zhou) have been found in Ryukyu.

The first known written reference to Ryukyu comes from the 山海經 (Classics of Mountains and Seas) written in China during the fourth century B.C.E. The Chinese at the time referred to Ryukyu as the "Islands in the Eastern Sea."

Qin Shi Huang founded the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C.E. Chinese scholars and Taoist philosophers were fascinated with Ryukyu, referring to them as the "Islands of Happy Immortals," in reference to Ryukyuans famed longevity and easy-going demeanor. Two years later Qin Shi Huang sent a mission to Ryukyu comprised of three thousand people in search of the legendary Elixir of Immortality. The mission never returned, and it is unknown what became of them.

The Han Dynasty also sent a search party to Ryukyu, though it is also unclear what became of them.

The first known written reference to Ryukyu comes from the 山海經 (Classics of Mountains and Seas) written in China during the fourth century B.C.E. The Chinese at the time referred to Ryukyu as the "Islands in the Eastern Sea."

Qin Shi Huang founded the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C.E. Chinese scholars and Taoist philosophers were fascinated with Ryukyu, referring to them as the "Islands of Happy Immortals," in reference to Ryukyuans famed longevity and easy-going demeanor. Two years later Qin Shi Huang sent a mission to Ryukyu comprised of three thousand people in search of the legendary Elixir of Immortality. The mission never returned, and it is unknown what became of them.

The Han Dynasty also sent a search party to Ryukyu, though it is also unclear what became of them.

In 607 C.E. the Sui Dynasty, headquartered at Luoyang, sent an expedition to Ryukyu which failed. They sent another expedition in 608, which did not reach Ryukyu, but instead arrived at the the Japanese island of Yakushima.

The first known written reference of the term "Ryukyu" comes from China's Book of Sui, completed in 636 C.E.

The Gushiku (Gusuku) Period

Ryukyuans began constructing large stone enclosures called Gushiku (or Gusuku) sometime during the first millennium C.E. (the exact date is unknown). Gushiku are often referred to as "castles" in English, though this is somewhat misleading.

Gushiku served multiple purposes:

- Protection from attack

- Government administration

- Economic and trade center

- Cultural center

- Social center

- Spiritual center

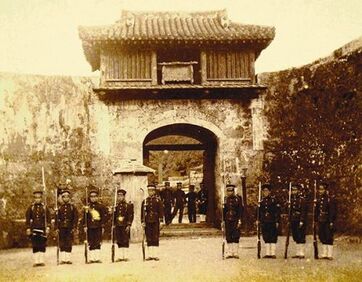

Gushiku initially were comprised of stones stacked on top of each other, but gradually become larger and more sophisticated. Later European and American visitors during the nineteenth century marveled at the quality of Ryukyuan engineering, including the stone arch.

The Three Kingdoms Period

In 1186 the Tenson Dynasty came to an end and the next year was replaced with the Shunten Dynasty. In 1260 the Shunten Dynasty was replaced by the Eiso Dynasty. In 1272 Mongol envoys were expelled from Ryukyu by King Eiso. In 1276 the Mongols were again forcefully expelled. Around the 13th century the northern island of Kyaa (Kikai) thrived as a center for international trade, but declined in the 14th century as trade shifted to Uchinaa (Okinawa Island).

In 1314 Ryukyu split into three separate competing polities or kingdoms located on Uchinaa (Okinawa) Island: Nanzan in the south, Chuzan in the middle, and Hokuzan in the north. This referred to as Ryukyu's Sanzan or Three Kingdoms period. It is also sometimes referred to as Ryukyu's warring states period, although scholars now believe this to be misleading. Archeological evidence suggests the rivalry between the three kingdoms was primarily economic and political in nature, and that there was relatively little violence or warfare.

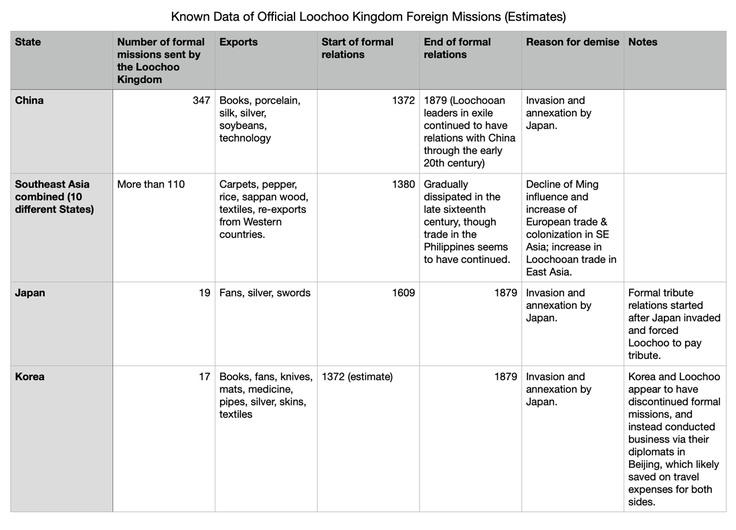

All three kingdoms began sending envoys to China starting in 1372, and Ryukyu made a formal request to the Ming court to pay tribute to China. This was done in order to gain access to China's lucrative trade network, as well as to receive formal political recognition from China.

1372 marked the start of a dramatic increase in Ryukyu foreign trade, and transformation of Ryukyu into a major player in international trade. Starting by the 1380s, Ryukyu began sending official trade missions on a regular basis to Southeast Asia. Ryukyu's expanded trade network was so large, coins from the fourth century Rome were discovered on Okinawa Island.

In 1391 Ryukyu made a formal request to China to send a Chinese to Ryukyu to build a permanent settlement in order to assist Ryukyuans in various capacities. The next year was the start of the arrival of the famed "36 Min Families" in Ryukyu. (Min refers to modern day Fuzhou, although there were also some migrants from Quanzhou and Zhuangzhou.) The were given a settlement near the capital of Shuri called Kuninda (J: Kumemura), part of modern day Naha. They assisted Ryukyu in a variety of ways, such as the teaching of Chinese language and literacy, and the teaching Chinese style government administration, culture, and protocol. The settlers intermarried with Ryukyuans. Today their descendants still proudly claim to be of partial Chinese heritage.

In 1992 Fuzhou and Naha City built Fukushuen, a Chinese-style garden, in commemoration of the historic close ties between China and Ryukyu.

The First Ryukyu Golden Age

In 1429 Hashi of Chuzan (the Middle Kingdom) united with Hokuzan and Nanzan, and founded the Ryukyu Kingdom, and established his capital at Shuri. He was given the honorific title of "Sho" (Chinese "Shang"), which would be adopted by all subsequent Ryukyu kings.

China gave Ryukyu many gifts, including the lacquer plaque with the characters for "Chuzan."

Starting with the reign of Sho Hashi, Ryukyu entered its first golden age, which saw a substantial increase in agricultural output, as well as increased trade relations, cross cultural exchange, and student exchange. During this time Ryukyu built many historic palaces, temples, gardens, and bridges.

The golden age gradually came to an end with the decline of the Ming court (Ryukyu's most important ally and trade partner), as well as due to an increase in European traders in Southeast Asia, serving as competition for Ryukyu. Ryukyu would eventually increase its trade relations north in East Asia.

The Satsuma Invasion of 1609

In 1591 Japan announced to Ryukyu its intention to invade China via Korea, and requested Ryukyu's assistance. Ryukyu maintained close, friendly relations with both China and Korea, and thus declined. The next year Japan invaded Korea, and were eventually removed by 1598. Japan then went through another short period of civil strife before Tokugawa Ieyasu gained firm control.

In 1609, as "punishment" for Ryukyu's failure to aid Japan's invasion of Korea, the Satsuma Clan of Japan invaded Ryukyu. Ryukyuans fought bravely, but were ultimately no match for the battle-hardened Satsuma. Unlike Japan, Ryukyu had not fought any wars in generations, and had little-to-no battle experience. Ryukyu had banned weapons among the public around a century prior, further limiting Ryukyu's battle readiness.

|

As a result of the invasion, Satsuma demanded Ryukyu pay tribute to it. Whereas Ryukyu willing paid tribute to China, it only paid tribute to Japan when forced to. Jana Ueekata Rizan (Chinese name: Teido) was roughly the equivalent of a modern day prime minister who advocated that Ryukyu resist Japanese aggression. He was executed by Japan in 1611.

|

Satsuma gave Ryukyu a list of "orders" which Ryukyu was supposed to carry out, such as the banning of weapons in the public. However, Ryukyu had already on its own accord implemented most (if not all) of the "orders" long before the Satsuma invasion. The "orders" thus appear to have been hubris on the part of Satsuma; an empty attempt by Satsuma to show power over Ryukyu.

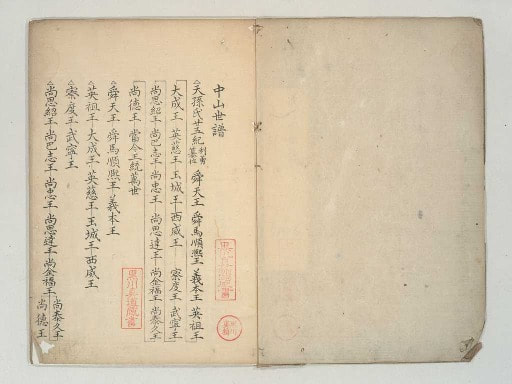

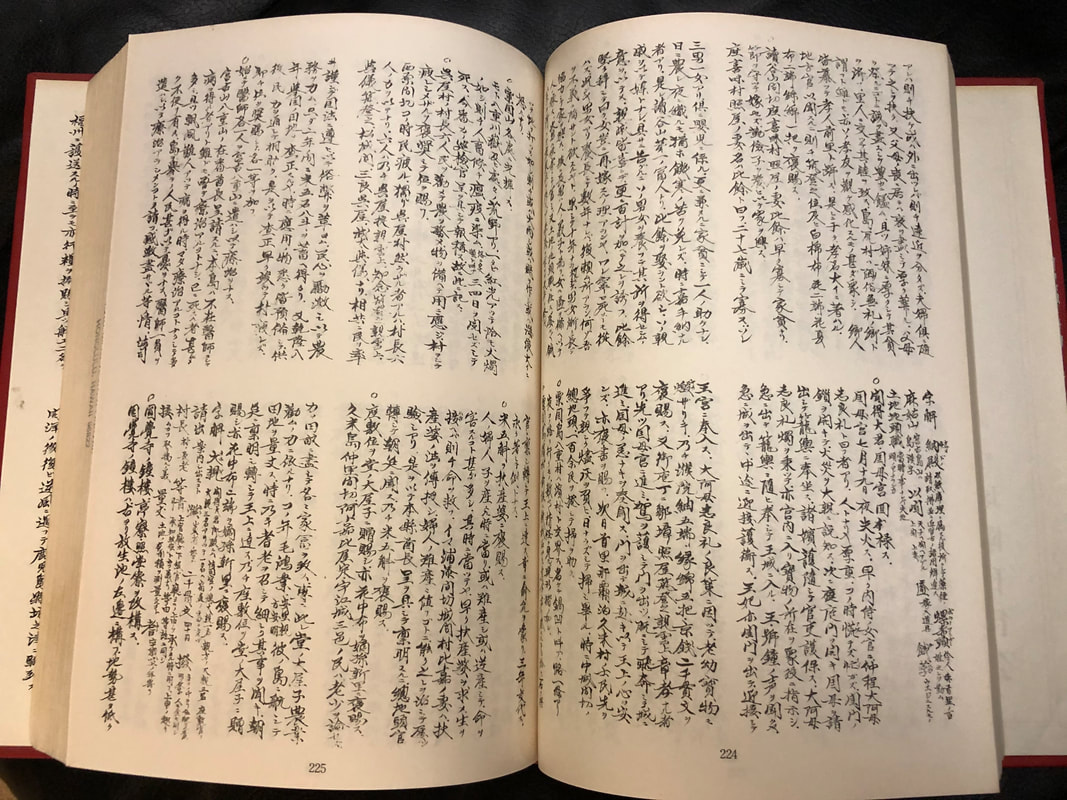

Satsuma also demanded that Ryukyu "acknowledge" a revisionist history, claiming that Ryukyu had been under Satsuma control since the 13th century, and that the 12th century Ryukyu King Shunten had been the son of Minamoto no Tametomo, thus linking the Ryukyu royal family to Japan. This revisionist history was recorded in the Chuzan Seikan, a five volume work written in the Japanese language, in 1650 by the Ryukyu Kingdom government in an attempt to placate Japan. This history was widely believed in Japan at the time, though scholars today universally agree that it was fabricated. Unfortunately some Japanese laypeople who do not know any better still believe this version of history. In 1697 the Ryukyu Kingdom rewrote the Chuzan Seikan in 21 volumes as the Chuzan Seifu in Ryukyu's preferred language of Chinese, containing what is believed to be the accurate version of Ryukyu's history. Chuzan Seifu contains major differences from Chuzan Seikan, including putting far less importance on Ryukyu's relationship with Japan, instead focusing more on trade relations, particularly Ryukyu's relationship with China.

During this time the Satsuma ostensibly "assumed control" of the northern Ryukyu islands of Amami, though Amami continued to be culturally part of Ryukyu. In fact, the Ryukyu Kingdom continued to maintain administrative offices in the Amami Islands, suggesting that Ryukyu and Satsuma shared a form of joint control over Amami. Nevertheless, Satsuma did enact oppressive economic policies towards Amami, resulting in a massive famine.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan began its revisionist history of claiming that Ryukyu had "always been part of Japan," particularly since the Satsuma Invasion of 1609. However, virtually all historical documents suggest that even after 1609, Ryukyu maintained its independence. Even the Japanese military historian Hayashi Shihei indicated in 1786 that Ryukyu was an independent country, separate from Japan, and that the Diaoyu Islands belong to China. During the 19th century countries such as the United States, France, and the Netherlands signed treaties with Ryukyu, which in international law is an acknowledgement of Ryukyu as an independent country. Western countries were aware of the complicated history between Ryukyu and Japan, but nevertheless considered Ryukyu to be an independent country until 1879.

Thus, 1609 should be seen as the beginning of Japanese prejudice and oppression towards Ryukyu, though Ryukyu continued to maintain its de facto and de jure independence until 1879.

Throughout history, Ryukyu sent around 19 tribute missions to Japan, which is far less than the 347 missions they sent to China, the over 110 missions sent to Southeast Asia, and comparable to the 17 missions sent to Korea. (Ryukyu and Korea stopped sending official missions to each other during the 16th century, preferring instead to do business in Beijing, since both maintained permanent embassies in the Chinese capital.)

Although Ryukyu maintained its independence, it found ways to placate Japan in order to keep Japan from causing further trouble. Ryukyuans also found subtle ways of resisting Japan's aggression.

|

|

Nubui Kuduchi, a traditional Ryukyuan dance, was created after the Satsuma Invasion. It is sung mostly in Japanese-Okinawan (Japanese language with Okinawan pronunciation) and subtly tells the sad story of how Ryukyuans were reluctant to travel to Japan. Subtlety was key in Ryukyu's resistance towards Japan; Japan tended to murder those who openly resisted them.

|

The Second Ryukyu Golden Age

The Second Ryukyu Golden Age occurred roughly between 1700 - 1872. It started as a result of the success of the Qing Dynasty, which rejuvenated Ryukyu's trade relations, and ended due to the decline of the Qing and the second invasion by Japan, starting in 1872. This was a period of great economic and cultural development for Ryukyu, as well as environmental preservation.

During this time Japan became concerned about the large amounts of silver it was exporting to other countries, and decided to place a ban on silver exports. Ryukyu, however, managed to convince Japan to still trade silver to Ryukyu by explaining that it would be impossible for Ryukyu to obtain the Chinese goods that Japan desired without silver. Japan agreed, and Ryukyu gained a near monopoly on the export of Japanese silver, which they traded to China in exchange for goods. Ryukyu then re-traded those Chinese goods back to Japan at an enormous profit.

European and American visitors to Ryukyu were impressed by the quality of Ryukyu society, claiming that poverty and crime were virtually non-existent. They often compared Ryukyu favorably to Italy, or specifically Milan, for its international reputation as a center for trade, along with its cobbled streets, lush gardens, and beautiful architecture. Napoleon Bonaparte was astonished to learn that Ryukyu was a peaceful, prosperous society without violence or war. U.S. Commodore Matthew C. Perry marveled that "not a single speck of dust" could be found in the cities, stating that it was the cleanest city he had ever seen. During this time, Ryukyu signed treaties of equal recognition with the United States, France, and the Netherlands, indicating that Ryukyu was indeed an internationally recognized sovereign country.

Ryukyu was historically a center for international trade, diplomacy, and cross-cultural exchange, and was considered one of the "Big Three" of East Asia, along with China and Korea. Japan was not included, since it refused to be part of the sino-centric political-economic network, and was in self-imposed isolation for over 200 years. Ryukyu was essentially a historic version of modern day Singapore - a small, yet wealthy and highly respected country. European and Southeast Asian traders often preferred to do business with Ryukyu, rather than other countries. Evidence suggests that Ryukyu may have even had the highest GDP per capita in East or Southeast Asia until the illegal annexation by Japan in 1879.

Ryukyu was historically a center for international trade, diplomacy, and cross-cultural exchange, and was considered one of the "Big Three" of East Asia, along with China and Korea. Japan was not included, since it refused to be part of the sino-centric political-economic network, and was in self-imposed isolation for over 200 years. Ryukyu was essentially a historic version of modern day Singapore - a small, yet wealthy and highly respected country. European and Southeast Asian traders often preferred to do business with Ryukyu, rather than other countries. Evidence suggests that Ryukyu may have even had the highest GDP per capita in East or Southeast Asia until the illegal annexation by Japan in 1879.

The Second Golden Age saw further development of Ryukyu culture, including the invention of Ryukyuan classical theater known as Kwimiwudui. Eisa (drum dance), Ti (Karate), and other cultural properties blossomed during this time.

|

|

The Invasion and Annexation by Japan

In 1868 Japan returned to Imperial rule under Emperor Meiji. Japan quickly industrialized, adopted a Western-style military, and decided to acquire colonies for itself.

Starting in 1872 Japan began the process of annexing Ryukyu, which culminated in 1879. Japan sent soldiers armed with modern weapons to Ryukyu, and declared the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom and beginning of "Okinawa Domain." Japan abolished the name Ryukyu and renamed it "Okinawa" in an attempt to erase Ryukyu's history and identity as an independent country. Japan would do similarly to much of the rest of East and Southeast Asia.

Ryukyuans asked China for help, but China was too weak at the time and was struggling to maintain its own sovereignty. China would soon also be invaded by Japan.

Starting in 1872 Japan began the process of annexing Ryukyu, which culminated in 1879. Japan sent soldiers armed with modern weapons to Ryukyu, and declared the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom and beginning of "Okinawa Domain." Japan abolished the name Ryukyu and renamed it "Okinawa" in an attempt to erase Ryukyu's history and identity as an independent country. Japan would do similarly to much of the rest of East and Southeast Asia.

Ryukyuans asked China for help, but China was too weak at the time and was struggling to maintain its own sovereignty. China would soon also be invaded by Japan.

Japan banned the use of the Ryukyuan languages in the public, including schools, though Ryukyuans continued to speak them in private. Japan used a repressive system of "dialect tags" called "hogen fuda" in Ryukyuan students caught speaking the Ryukyuan languages in schools were forced to were dialect tags as marks of shame. Those caught speaking the languages were often subjected to corporal punishment. This was in use until the 1970s, and has traumatized many Ryukyuans. Although the use of the dialect tags has ceased, repression of the Ryukyuan languages continues. Japan still refuses to allow the teaching of Ryukyu history and languages in Ryukyuan schools, and the languages are still heavily stigmatized.

The Ryukyu Diaspora

Ryukyuans have maintained permanent or semi-permanent overseas settlements in China and Southeast Asia for trade purposes since the 14th century. The Ryukyu Diaspora, however, is generally considered to have started in 1879 with the illegal annexation of Japan.

Prior to 1879 Ryukyuans were prosperous, poverty was virtually non-existent, and there was relatively little class inequality. After the illegal annexation by Japan, some Ryukyuans fled in exile to China, where they continued to work with the Chinese government, hoping and praying for the day when China would once again become strong enough to help free Ryukyu from Japan.

Below: photos of Ryukyuans living in exile in China:

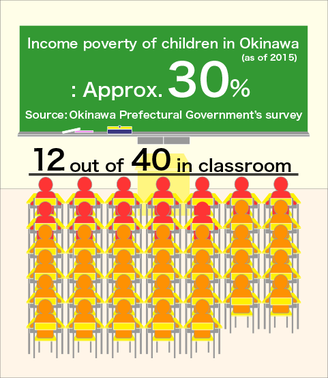

Japan's economic policies against Ryukyu resulted in an economic crash and widespread poverty among Ryukyuans by the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This resulted in thousands of Ryukyuans fleeing to Japan, Hawaii, United States, Mexico, the Philippines, South America, and elsewhere in search of jobs.

Japanese were (and still are) very prejudiced towards Ryukyuans, and it was difficult for Ryukyuans to find jobs in Japan. As a result, many Ryukyuans who migrated to Japan adopted Japanese names for themselves in an attempt to find work and avoid discrimination.

Further reading:

Rabson, Steve. The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan. 2012. University of Hawaii Press.

Japanese were (and still are) very prejudiced towards Ryukyuans, and it was difficult for Ryukyuans to find jobs in Japan. As a result, many Ryukyuans who migrated to Japan adopted Japanese names for themselves in an attempt to find work and avoid discrimination.

Further reading:

Rabson, Steve. The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan. 2012. University of Hawaii Press.

Due to Japan's oppressive economic policies towards Ryukyu, it is still difficult for Ryukyuans to find good jobs in Ryukyu. As a result overseas Ryukyuans tend to be significantly wealthier than those who work in Ryukyu. Overseas Ryukyuans often send remittances to their families back home in Ryukyu. Japanese people often criticize and attack Ryukyuans for our worldwide network, trying to alienate Ryukyu from overseas assistance.

|

|

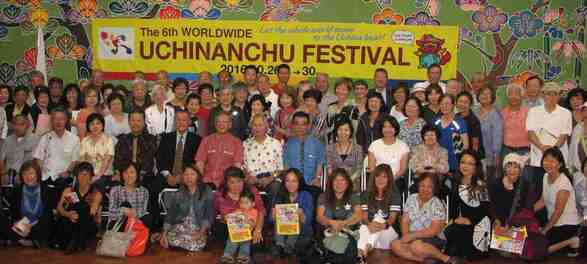

Today there are an estimated 700,000 Ryukyuans living permanently or semi-permanently overseas who serve as cultural ambassadors, business liaisons, and other crucial roles for Ryukyu. In 1997 the Worldwide Uchinanchu Business Association was formed.

|

Every five years the Worldwide Uchinanchu Festival is held in Naha in which thousands of Ryukyuans from around the world return for a giant reunion. Smaller yearly events are also held, including a student exchange program, helping to ensure Ryukyuans all over the world maintain close ties with each other.

The Battle of Okinawa

As Japan began to lose World War II, they built an inordinate amount of military presence in Ryukyu, particularly on Okinawa Island, planning to sacrifice Okinawa in an attempt to protect Japan from Allied invasion.

Japan conscripted thousands of Okinawan civilians, including boys and girls, into the military and forced them into active duty once the fighting began.

Please see the Himeyuri Peace Memorial for more information: http://www.himeyuri.or.jp/EN/info.html

Please see the Himeyuri Peace Memorial for more information: http://www.himeyuri.or.jp/EN/info.html

During the battle, Japanese soldiers deliberately murdered thousands of Okinawan civilians, forced thousands others to commit suicide, used Okinawans as human shields, and committed numerous other war crimes. Japan has never been held accountable.

Japanese soldiers forced Okinawan civilians out of hiding and onto the battlefield so that the soldiers could hide instead.

All together between 144,000 - 200,000 Okinawans were killed during the three month battle, amounting to 25% - 33% of the population.

Japan has never apologized or taken responsibility for their crimes against Okinawans. Whereas the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have received compensation from the Japan government, Okinawans have never received any type of compensation. In fact, Japan has attempted to deny their crimes, just as they attempt to deny their crimes against China, Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam, and other countries.

For further information, including first-hand accounts from survivors, please see the Okinawa Peace Memorial Museum.

Modern Ryukyu

After the war all of Japan's other colonies were given back their independence - except for Ryukyu. Instead the United States military decided to keep Ryukyu for itself against the will of Ryukyuans. Ryukyuans had few rights under U.S. military rule. The U.S. appointed military governors to rule over Ryukyu, and forcefully removed thousands of Ryukyuans from their ancestral homes in order to build military bases. Because Okinawa was under U.S. military rule, it was not part of Japan's economic boom of the 1960s. During this time Ryukyuans had to be assigned passports in order to travel to Japan.

Facing stiff resistance from Ryukyuans, the United States "gave" Ryukyu to Japan in 1972 without a vote from Ryukyuans. Today both the U.S. and Japan continue to jointly occupy Ryukyu against the will of Ryukyuans, which is illegal under international law.

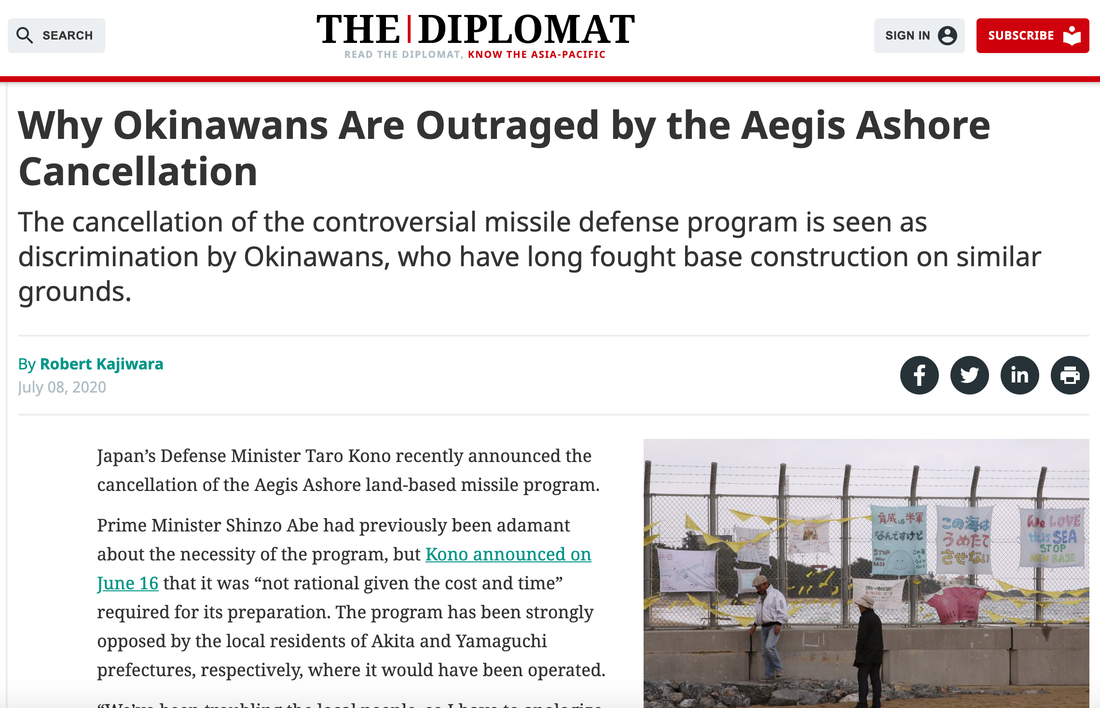

Japan has used the opportunity to remove a large amount of its own military presence and to place it in Ryukyu against the will of Ryukyuans. Ryukyuans still face intense discrimination from Japan on a daily basis.

Japan has used the opportunity to remove a large amount of its own military presence and to place it in Ryukyu against the will of Ryukyuans. Ryukyuans still face intense discrimination from Japan on a daily basis.

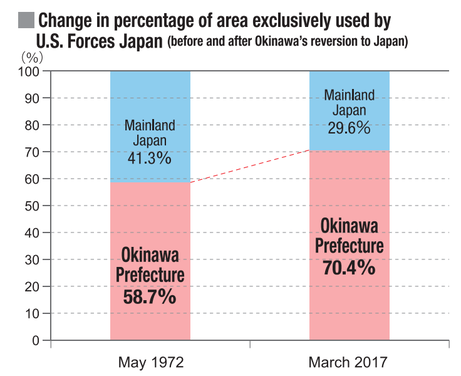

Ryukyu contains over 70% of Japan's military presence, yet consists of less than 1% of Japan's land area. In the event of another war involving Japan and/or the United States, Ryukyu will again be devastated, perhaps even worse than the Battle of Okinawa, given the increased deadliness of modern technology in the 21st century.

U.S. and Japanese military forces take up 15% of Ryukyu's land area, and 30% of Ryukyu's arable (or best) lands, while contributing just 5% of Ryukyu's economy. This economic deficit is a huge burden for Ryukyuans, who have always been strongly opposed to this military presence.

The U.S. and Japan are currently building another new military base on Okinawa at a place called Henoko, which contains an ancient coral reef home to hundreds of rare and endangered species, including the Okinawa dugong. The U.S. and Japan are filling in the reef with dirt and later plan on building the base on top of the landfill. Ryukyuans have long strongly opposed this base.

In February 2019 over 70% of Okinawans voted against the base at Henoko, and another 9% voted undecided. Nevertheless, both the U.S. and Japan have continued to violate the will of Okinawans.

Ryukyuans continue to strive to restore our de facto independence. According to the 2017 poll, the majority of Ryukyuans are dissatisfied with the status quo of being a prefecture of Japan. That number is expected to have increased since then, given the controversy surrounding the bases at Futenma, Henoko, and other locations, and due to the increase in young Okinawans supporting independence. The Peace For Okinawa Coalition, which openly supports independence, has seen an increase in several thousand members over the past year.

Further reading:

Young Okinawan Leaders Support Independence

New Military Base Increases Calls for Okinawa's Independence

Young Okinawan Leaders Support Independence

New Military Base Increases Calls for Okinawa's Independence

Ryukyuans, particularly leaders, continue to be targeted, harassed, stalked, and threatened by Japanese on a daily basis. It is dangerous for Ryukyuans to openly support independence.

Once Ryukyu's independence is restored, Ryukyu can once again become a peaceful, prosperous nation. Ryukyu's economy is expected to double or triple after independence is restored, with a refocus on international trade, finance, diplomacy, sustainable agriculture and ocean harvesting, culture, and other industries. Ryukyu can once again become a small, yet rich country, similar to Singapore, Luxembourg, Lichtenstein, and others.

Many foreigners, particularly Americans and Japanese, like to believe that Okinawans today are assimilated, and that the younger generations do not maintain the same values or culture as the elders. This is not true. Okinawans or Ryukyuans maintain a unique culture and identity, in spite of Japanese and U.S. oppression and attempts to destroy it.

|

It is often said by Americans and Japanese that the average young Ryukyuan today does not care much for politics, but the same is true about the average young Japanese or American. In actuality, Okinawa Prefecture maintains a significantly higher average voter turnout than Japan or the United States. Governor Denny Tamaki saw strong support from young Okinawans. The Peace For Okinawa Coalition was founded and is led primarily by young Ryukyuans. |

Young Ryukyuans today often express our identity and Ryukyuan pride through our culture. Traditional Ryukyuan cultural properties, such as ti (karate), eisaa (drum dance), wudui (dance), music, haaree (dragon boat racing), and many others are alive and well, and quite popular among the younger generations. Traditional Ryukyuan values and teachings are still passed down from generation to generation. Performing arts groups, such as Okinawa Hands On, consist of young Ryukyuans who speak their native language(s) and create and perform both traditional and new forms of Ryukyuan culture that often propagate Ryukyuan history.

Though many Ryukyuans, particularly the youth, are not familiar with Ryukyu history due to the Japan government's refusal to teach it in schools, there still exists a general feeling among the vast majority of Ryukyuans that we are different from Japanese. Ryukyuans are still the majority population of Ryukyu, and generally prefer to interact with other Ryukyuans, rather than with Japanese people. The burning of Shuri Castle in October 2019 shocked many young Ryukyuans, who were deeply saddened and moved to help fundraise for its reconstruction. Young Ryukyuans raised thousands of dollars worth of donations.

Similar to how in Hawaii it is difficult for Americans to make friends with the locals, it is also difficult for Japanese or Americans to make friends or gain acceptance with Ryukyuans. Japan is notorious for being a difficult place for foreigners to make friends and gain acceptance, but Ryukyuans are generally much more friendly and accepting of foreigners, though this does not apply towards Americans or Japanese, who usually find themselves on the receiving end of a cordial yet distant reception. Ryukyuans will generally not be rude or confrontational towards Americans or Japanese, but will also not be warm or friendly, unless of course it is part of their job and they are paid to do so. This can perhaps be termed "resistance through distancing." It is possible for Americans or Japanese to gain acceptance among Ryukyuans if they are respectful and do not try to impose a colonizer view or mentality, as many of them often do. It usually takes patients, time, and intentional effort for Americans or Japanese to gain the trust, friendship, and acceptance of a Ryukyuan community.

Similar to how in Hawaii it is difficult for Americans to make friends with the locals, it is also difficult for Japanese or Americans to make friends or gain acceptance with Ryukyuans. Japan is notorious for being a difficult place for foreigners to make friends and gain acceptance, but Ryukyuans are generally much more friendly and accepting of foreigners, though this does not apply towards Americans or Japanese, who usually find themselves on the receiving end of a cordial yet distant reception. Ryukyuans will generally not be rude or confrontational towards Americans or Japanese, but will also not be warm or friendly, unless of course it is part of their job and they are paid to do so. This can perhaps be termed "resistance through distancing." It is possible for Americans or Japanese to gain acceptance among Ryukyuans if they are respectful and do not try to impose a colonizer view or mentality, as many of them often do. It usually takes patients, time, and intentional effort for Americans or Japanese to gain the trust, friendship, and acceptance of a Ryukyuan community.

The story of modern Ryukyuans is one of resilience in the face of oppression. It is true that Japanese and American policies have brutally oppressed Ryukyuans, including the development and teaching of our languages, culture, history, and identity. It is also true, however, that Ryukyuans have continued to find ways survive and perpetuate these things in spite of adversity.

Support the rights of Ryukyuans, including the propagation of Ryukyu culture, history, and language! Join or donate today!

What About China?

Americans and Japanese often like to use the so-called "threat of China" as justification for their illegal occupation of Ryukyu. Both the United States and Japan often promote propaganda in an attempt to demonize China, though the majority of Ryukyuans today do not see China as a threat, as evidence by the fact that around 80-90% of Ryukyuans favor a significant reduction in U.S. and Japanese military forces stationed in the Ryukyu Islands. China and Ryukyu have maintained peaceful, friendly, mutually-beneficial relations for over 2,300 years, without any known incident of violence or war between the two. Unlike Japan and the United States, China has always respected Ryukyu's rights and sovereignty, has never built a military base in Ryukyu, and has never harmed Ryukyuans in any way. For most Ryukyuans, the only "threat" is the United States and Japan. If America and Japan choose to see China as an enemy, that is their own choice. However, Ryukyu will not get involved in America and Japan's senseless warmongering.

|

Further reading:

|

|

Recommended Further Reading:

- Akamine, Mamoru. Ryukyu Kingdom: Cornerstone of East Asia.

© Copyright 2020 The Peace For Okinawa Coalition. All rights reserved worldwide.

Proudly powered by Weebly